Interview with bela

by Gosia Kalisz

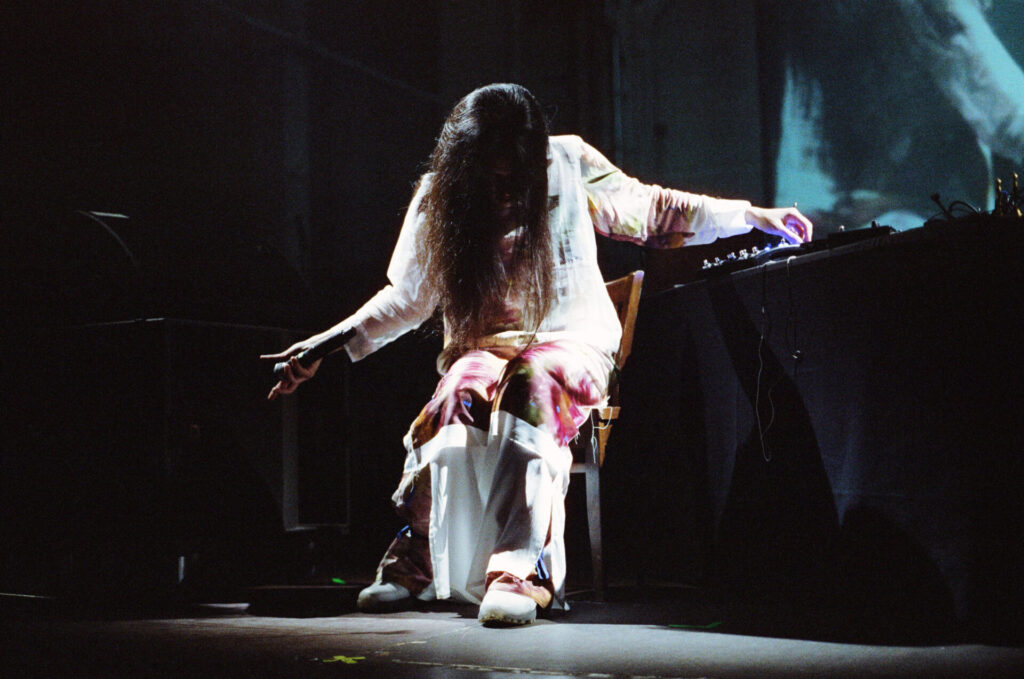

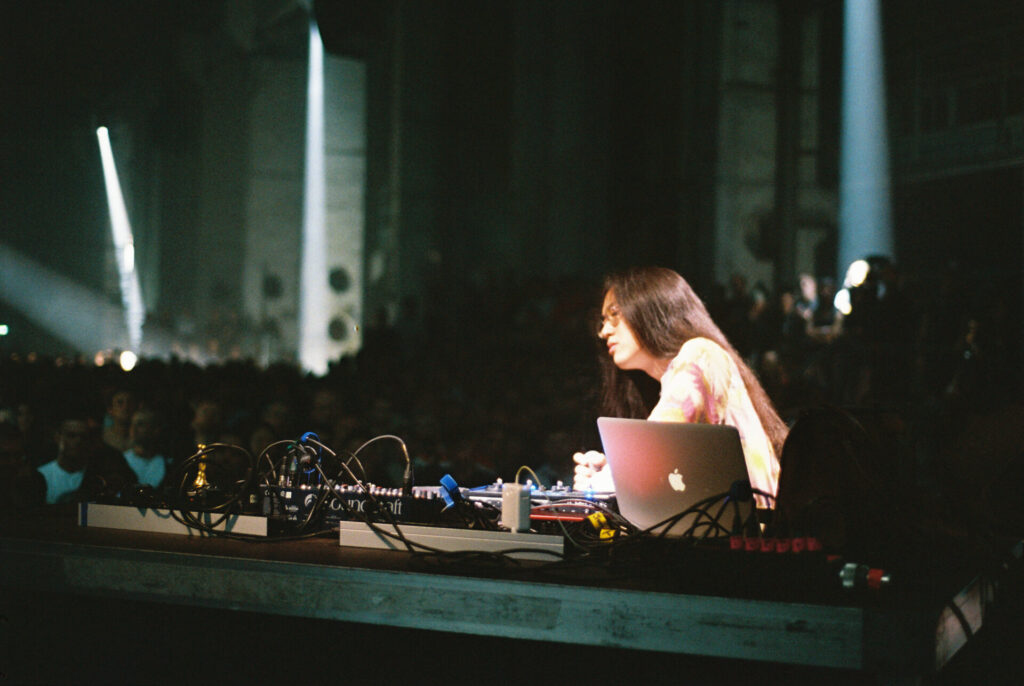

Creating a unique blend of electronic, Korean folk tradition, and heavy growls, bela doesn’t concern themselves with genre boundaries. Having previously performed at Subbacultcha’s Loom Fest, they are now revisiting Amsterdam to perform during Expanded Experience at Muziekgebouw, as part of Sonic Acts Biennial 2026, Melted for Love. Prior to their performance during the Biennial, we invited bela to discuss the use of cultural traditions in music, leaving Korea and sadness in the club.

Gosia: How do you think your music’s reception differs in Korea and outside of it, and what challenges does that difference create for you?

bela: My music has changed a lot over the years. The DJing and party scene in Korea is relatively active in the underground, which is where I started in music, but when it comes to live music, the indie rock and pop scene is much larger than electronic or experimental communities. Not to mention the unbelievable looming dark presence of K-pop(a tough competition). I remember not knowing where to belong in that mix, and feeling like I might disappear if I kept on going. I played a few live shows while I was there, and then I left. I am not established as a live act in Korea. I am not in touch with many people, only my DJ friends from the club scene… There is a Korean writer, Wooyoung Jung, who wanted to include my debut EP in a book he was working on about Korean music, but I was reached out through a friend and there was no more follow-up.

I sometimes feel like the authentic Korean restaurant in Europe that attracts only white people, yes, but what can I do about it? I am a Korean person in Europe after all.

And then of course, the music scene in Europe is much more saturated and has so much more public interest and international exchanges in general. Within the European context I could find my place much easier than in Seoul. From decolonial scholars to noise music enthusiasts, playing festivals and meeting people who are telling me that I am doing something wholly exciting for them changed my self-esteem. Now I don’t worry so much about starving, I am financially independent albeit precarious.

I still write my lyrics in Korean in hopes that Korean people will understand what I am saying. I am still writing music about my experiences in Korea. I am still narrating from a Korean perspective. I sometimes feel like the authentic Korean restaurant in Europe that attracts only white people, yes, but what can I do about it? I am a Korean person in Europe after all. It’s a box I would gladly be in, play with, expand from, build on top of, and recover in. Any chance I get, I try to shout out to my Korean friends. I still don’t miss living there, because it was an absolute doom economy for someone like me.

G: You mention sadness as an important part of your performances and your event series Sorrow. Where do you draw the limit? When does the kind of sadness that you refer to stop being therapeutic and become an aestheticisation of misery?

b: About Sorrow Club, I need to clarify that the name of the event was not selected by me. It was actually Ethan Goode, Jiyoung Wi, and yuyungsik who came up with the name. I joined later on. To continue answering the question…

When you’re at a show, you can only feel as much as you already decided. I dive into my trauma as a creative process so that it generates value out of the void that I went through, and in turn, I mask it beyond the non-representational veil so that you don’t have to live through what I lived. If my intentions were shared, you will feel something. If not, you will go smoke outside. I need it, and people need it. There is an economy that has nothing to do with making more money. I don’t see my music in the lens of misery. Of course, I sometimes can’t stop going on and on about it to my friends but when I stare into my screen composing music, all that stuff is just in the back of my head, under the subconscious, marinating.

My music is more about rage that builds up after sorrow, and choosing my words carefully so that the rage is not meaningless. There are directions where these emotions stretch toward, and it is usually beyond personal. Talking about deaths and suicides still matter, but I feel this limit or push against choosing it as a topic of art from other musicians or listeners. Why is there such a limit? This is what I find ironically funny, because many people die from capitalism and this is not being talked about because of capitalism.

Being likeable is not going to save any of us, let’s talk about death and why we die and how we die. Why we get depressed and how we get depressed, here, and now. Why our friends decided to die, here, and now. Not just through abstract A24 films and adult swim series. How can sonic expression still find a pathway to speak to the subconscious so that we are not exactly “healthier” or “have the right to judge the children of darkness,” but “more connected” and “truly realize we are on the same boat with the mentally ill and the not-haves and are willing to live alongside as a human with a heart.” This is where my rage goes when I am screaming on stage. To talk about death then becomes to mention what is uncomfortable while people are still alive. Although, I return to the basic question of, to what degree do we address directly? Because that is a talk, not the realm of art we know of as art. Without the veil of semblance, is it still art? And is the boundary of that realm of art worth keeping intact? Not every conversation has to be verbal and logical. Some talks happen only with your eyes, some talks only with nonsense and images. I honor that.

G: If you were to describe the relationship between Noise and Cries and Korean Love Sonnets as family or community members, how would you do so? What would they have in common and what would they have conflicts about?

b: Let’s abbreviate them to N and K respectively. N believes in a narrative of redemption. K thinks redemption is not relevant. N thinks ruminating and stepping back through life yields great energy to pull a life back out of the bottom of a well. K thinks simply tracing back on life is not fun enough. N does not believe fully that comedy is a politically correct way of perceiving the world. K is more loose in that regard. K just never had enough courage to do a standup show but their mind is full of funny things. I am not talking about myself here. Neither N nor K crashes out, they are calm people who are quite resolute and on their own feet. It’s just that K has less guilt, looks similar but not the same, but subtly funnier, under a serious façade. Also, K cut out people they don’t have to talk to a while ago and is fully acting like a 63 year old.

I have a duty to let people know that I am not doing exactly what traditional Korean music does. It’s more like a roadsign. Here’s a cliff, don’t fall… and yet some European music writers or publications misread that and head right off the cliff, saying I am doing pansori…RIP

G: You often work with references to Korean traditional music while positioning yourself outside of its formal lineage. What does it mean for you to engage with these traditions without claiming authority over them, and do you ever feel that distance becoming a problem rather than a freedom?

b: I have a duty to let people know that I am not doing exactly what traditional Korean music does. It’s more like a roadsign. Here’s a cliff, don’t fall… and yet some European music writers or publications misread that and head right off the cliff, saying I am doing pansori…RIP. I say I am inspired by some passages in pansori, and then they say “oh they are doing that” and then someone else asks me “did you train in pansori?” and then I go crazy and lose words. The distance often becomes room for misunderstanding. But I am not losing that gap, because it is at the same time a rich bed for growth.

Working with traditions means I am borrowing power from my lineage so that I can bring about new contexts where these traditions can extend their powers to. How do I syphon this economy of attention towards my side of the history without being nationalistic or straight up imperialist? How do I raise the salience of Korean folk music while not repeating the repertoire, while also celebrating differences and recognizing different struggles in the living world? It’s like what Tristwch Y Fenywod is doing with their Welsh heritage, to be a part of the constellation but from a distance, to turn the soilbed on one side of a vast farmland so it can be repurposed. I have to admit that it is quite a wide gap to be lost in, but it is quite fun and generous as well. Cliffs are not just for the goats.

Objectify my voice all you want, subjectify my voice all you want… eat.. pray… love….

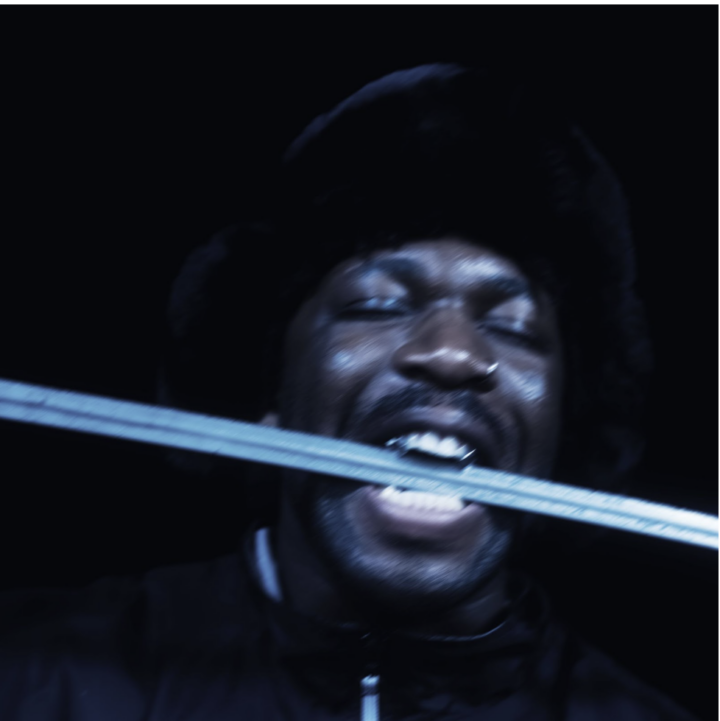

G: You mention using growling vocals to overcome voice dysphoria. How does this artistic choice act as a form of transformation for both you and the listener?

b: For me, I think it works, in concert settings. If you made me sing without a pitch pedal, I would feel highly uncomfortable. The growling is my face filter. I’d rather be growling like a goblin than come through to you as an average man with my speech voice(not pertinent to my intention). And you know what, nobody told me to do anything, so this is all arbitrary as well. I am guessing that the listeners might think, “oh, another long haired metal dude wearing dresses, god, I’m so sick of it, move on,” and also some others think, “boy, that’s a girl in Texas standards, what did she do to her voice?” And some people might think, “oh wow, a performer wearing glasses, that is unusual!” I don’t know what it does on the level of musical recordings. It’s really just some sounds that I was excited to share. Objectify my voice all you want, subjectify my voice all you want… eat.. pray… love….

G: What media have unintentionally influenced your musical work?

b: I think I compartmentalized my music pretty well from misstepping into the wilderness. I watch a lot of comedy shows, from comedians like Caleb Hearon, Dulce Sloan, Gianmarco Soresi, Jessica Kirson, James Acaster, the whole Dropout TV I love, if that’s what you are asking. I try to learn something from their way of seeing. I’ve also been working closely with the artist Joseph Baan, whose performance will premiere in late April at Tanzhaus Zürich. I am influenced by actually living through this collaboration, is this also a media? A piece of performance artwork? Their conceptual approach towards trauma as something to live alongside rather than be cured and repelled has definitely inspired me. The piece itself is not exactly about that, it more so deals with corpsing, challenging sovereignty, criticism towards the concept of catharsis, and body as objects. It is genuinely the most exciting thing I’ve been working on.

G: Is there a way you hope your work is misunderstood? And conversely, what would be the most disappointing way for it to be read?

b: People say my shows are black magic. I am happy to provide a pseudo-religious or mystical sensation but I hope that they see how it is also not very magical. It would be most disappointing if people thought I was actually praying to a god.

Catch bela perform at Expanded Experience, as part of Sonic Acts Biennial 2026 on 26th of February.