An Interview with HTRK

Written by Sanae Oujjit

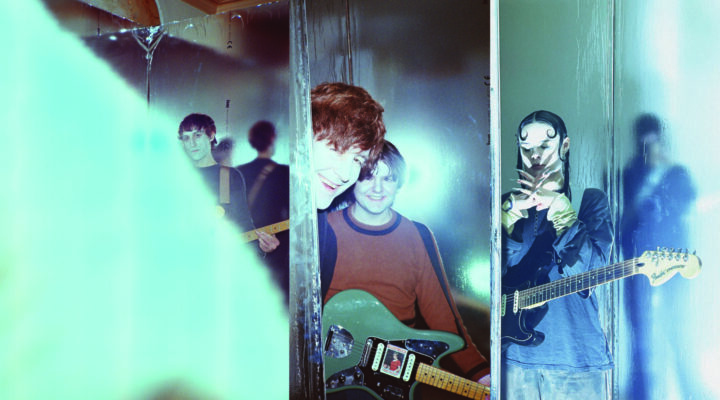

Friendship, in all its variety, is the driving force behind HTRK. Even though the duo often finds themselves on different paths, they always manage to intersect at the right moment. HTRK’s sound is gentle, soul-wrenching and indeterminate: a blend of two artists’ objective towards refinement. Ahead of their performance at Rewire Festival, on Friday April 7th, we spoke with Nigel Yang and Jonnine Standish about self-discovery, perfect simplicity and the pressure of time.

The melancholic vocals and sensual guitar strings of HTRK’s latest releases configure melodies that make the listener experience a multitude of emotions. There is especially a sense of carelessness present within your sound, but also lyrically. These emotions are not simply put in words. ‘Devil Do’ makes me see all the beauty in the world and simultaneously makes me want to throw my furniture out of the window. How did these distinct musical and aesthetic characteristics of HTRK come into being?

Jonnine: What is interesting about that particular demo is that it is the only nonsensical song we released—it consists of pre-lyrics. Rather than starting the writing process with written lyrics, Nigel and I have been trying to open the portal to being in the moment and see what wants to come out. Sometimes that happens effortlessly, even carelessly, and other moments it can feel forced. You kind of proved the point that lyrics are not always as important as they seem—it is more about the emotion and the tone that makes you want to throw your furniture out of the window.

Nigel: We like the effortlessness and the freedom that comes with being in the moment when making something, but we are also interested in perfectionizing simplicity. Simple things take a lot of work to get right, and other things are just about capturing it on tape until it feels right. Sometimes you catch a moment that you can not recreate—’Devil Do’ was never re-recorded.

J: We never even wrote it!

What led you to choosing the specific demos for Death is A Dream?

N: These were the songs we just had a fond memory of. Rhinestones took a lot of work and time—it was fun to just compile and release these other works.

J: It is almost more fun to go through every single demo without there being any emotion attached. In comparison to the refinement process of crafting an album. With the completion of an album it is nice to listen to your own work without judgment and pressure. We often find works that sound better than songs that made the album. The demos album has been a great opportunity to have a new release that is a bit looser, and a little more wild.

Are love and heartbreak generally the overarching themes?

J: Emotional themes have always been present within our work. Rhinestones specifically has been the first album wherein we investigated non-romantic relationships. We have been exploring all the different ways in which friendships are formed and lost. Friendships are equally as important and potent as romantic relationships—you experience all the similar emotions of loss, rejection and attraction. Rhinestones was delving into these friendship-related experiences. We’ve only scraped the surface of this imagery. With our upcoming work, we are delving deeper into this concept, as well as taking an interest in describing quite ordinary things and adding more imagery and description to them.

With your roots being in the DIY scene, do you still consciously choose to go for the DIY way, like the real headfuck / reverse deja vu cover art, with your visual imagery?

J: Nigel and I have done our own cover art and posters since the beginning—which I have predominantly occupied myself with. I was a graphic designer for a long time, I’m now a retired graphic designer (laughs) . We have been collaborating more with different artists lately; the Death Is a Dream artwork is made by the artist skkinz (@skkinz).

N: The real headfuck / reverse deja vu artwork was seemingly copied by Margiela. J: The different emoticons on the cover art of real headfuck / reverse deja vu embody the multiplicity of feelings—like deep loss with cuteness or really heavy feelings with softness—that are present within our songs. The exploration of emotions within our songs becomes more interesting when they coalesce with other emotions that usually don’t go together. This comes through in the graphics as well—a slight surrealism.

You mentioning surrealism reminds me of some mythical and biblical references I’ve noticed within your discography.

J: It’s interesting that you have noticed that. We like to send out secret messages to our fans. We feel very connected to them, and feel very aware of them. Most of them have been around for a long time. This is a way of communicating with them.

The soundtrack album Over the Rainbow for Jeffrey Peixeto’s Scientology documentary has some new age elements which I can also hear back in your latest folk ballads. Maybe it’s Jonnine’s repetitive meditations and/or Nigel’s gentle guitar strings. How has minimal sound impacted your creative process?

N: Peixeto’s direction was to make the music lighter—more hopeful. The documentary follows scientologists through rose tinted glasses. They see things through a beautiful and golden lens, almost kitsch, obscuring the darker sides of the world. With the focus on ascension—climbing the ladder to a higher level of being. Ambient and drone can easily have murky and ominous inclinations. That’s why it was helpful to get the direction to make something lighter or “spiritual” with Over the Rainbow, and this stuck with us. Actually, since our second album Work (Work, Work) I can hear an interest in spiritual growth. Every album has been a marking point of where we are on our paths to self-discovery.

The band was founded in 2003, it has been two whole decades. How has time influenced the way in which your project has evolved?

J: I’ve always wanted to be more prolific in the pace we would release. However you can not force these things to come out.

N: It’s hard to lose the pressure of time. But this pressure is not in the best interest of creating work. We have been conditioned to think that time equals money, or time equals structure. But time is a construct, reject it as much as you can.

With all these years of working together, how do you sustain both a healthy work and personal relationship?

J: I thought about it recently, and I think I know the answer to this question: radical acceptance of the present moment! (laughs). It’s a business in a kind of way—in a deep way and an emotional way. It is not just about the music, but also our communication about touring, shows, artworks, merchandise, a whole bunch of different things outside of music that we find enjoyable. When our opinions differ, I try to not be too emotionally invested in the outcome, because I kind of see us as one organism.

N: Even when we have slight disagreements, we know we will agree one hundred percent on the same decision.

J: We never try to talk each other into things.

N: And we are both sensitive to the psychology of someone we are working closely with.

Can you tell me something about the future of HTRK?

J: What we will do differently this time around is that we will share our creative process. However we don’t know where we are going to land sonically.

N: I think it is too early to say.

J: Everything is in the blender at the moment.

HTRK will be attending Les Becque’s Artist Residency on the shores of Lake Geneva where they will be writing and recording new material. On April 7th, they will present some of these new works at Rewire Festival in The Hague. Get your tickets here.