An Interview with KMRU

by Sydney van Nieuwaal and Thierno Deme

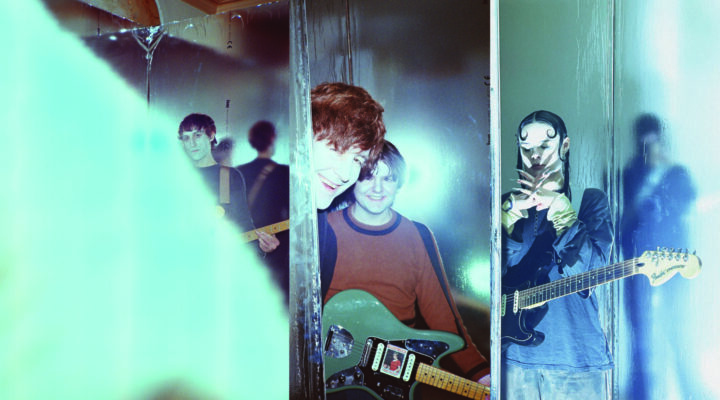

Photos by Marco Krueger

KMRU listens to cohere with that what’s around. Sometimes as an observant with bare ears, sometimes as a collector, documenting what passes by. KMRU’s re-sculpted collages, big or small, brim with details, props and pieces of decor. They capture reveries of another time, and especially of another place. We spoke with the sound artist and musician about era’s in one life, liminality and slowing down.

Sydney: Hi Kamaru. Thank you for speaking with us. This interview is held in the context of Subbacultcha’s magazine, Sprout. Each issue of Sprout explores a theme. This one’s ‘linger’. What does that word evoke to you?

KMRU: I think about it in connection to the word ‘stroll’. I think lingering can also be connected to listening very freely, to having an open mind. I think that’s what I connect with a lot.

Thierno: As I was going over your interviews I noticed that at different points, you would talk about having this desire to slow things down, whether that was the music you were making or the spaces you were residing in. What is it about the slower pace that appeals to you?

K: There’s always a rush in doing things. Sometimes when I’m walking I feel like things slow down. When I moved to Berlin, I felt a pressure to move quickly and to have things done very fast. Through my music, I try to invite the audience to slow down. For example, by making long durational pieces that make you feel grounded. I think that’s connected to walking. I’ve recorded a lot of footsteps, trying to find a connection to the pace of things. But, I’ve always had an interest in slowing things down. Even in my daily routine, to try and have a connection with change.

T: It’s a prerequisite to being able to take things in more and to process them in a way.

K: Yeah. By slowing down I can gain this panoramic view of what’s happening and take time to reflect upon it.

T: Could you interpret this ‘slowing down’ as a form of lingering in your own understanding?

K: I think the word linger does have a connection to slowness. I don’t think you can linger very fast. There’s days where you just want to let things happen and not force anything, and I think through slowness or lingering you’re able to be attuned to what’s happening in the environment. You’re able to leave room for things to happen.

S: Makes me think of walking into a room without light. You can’t see a thing, but if you just stay around for a bit you start seeing more. So, you talk about taking things slow, but you have a lot of musical output, relatively. Can you tell us a bit more about that as well? Are you aware of the vast quantity of your projects, or is it a very natural way of creating and releasing to you?

K: I’m quite aware, but at the same time it feels quite natural. I’ve been making lots of music, but I’m not trying to rush and release stuff. I just find myself with many tracks and projects that I’d want to put out there.

S: Your latest release is titled epoch. An epoch is a particular period of time in history or a person’s life. What makes you move into a new epoch, rather than stay and linger in one?

K: epoch was made in a really eventful time this year, when I was constantly on the move. I knew that during this period I wouldn’t have a lot of time to be home and make as much music as I did before. So, I scheduled one month to slow down and make music, to be released at the end of the year. epoch was an iteration of my musical process.

S: Do you see your projects as chapters that coincide with changes in your creative process?

K: It depends on the project. At some times I like being free in the process of making music, while at others I’m exploring something specific, that’s drastically different from the usual.

S: Your music can be of a very textural or atmospheric focus, rather than following a certain song structure. Sounds build, they take presence for a while, and fade away – either static or cyclical. When do you feel something’s finished?

K: For long durational pieces it’s like I’m trying to create this story or narrative by having elements enter, remain or fall apart. But, sometimes I want to make a long piece, but it ends up being finished at the one minute mark. I think I feel a piece is finished when it says what it wants to say.

S: Your project don’t linger, they might see you explores “sounds which are unseen, which are always in around us and mostly unnoticed. Although they are somewhat silenced; these sounds have a connection / interaction with the environment, just like our bodies.” Could you elaborate a bit more on the connection between silence, our bodies and the environment?

K: That project started around the time COVID kicked off. As I was at home a lot, I started doing lots of electromagnetic field recordings. Those enabled me to listen to unseen sounds. We are surrounded by hums, noises, frequencies and waves. I wanted to make a collage piece with different soundscapes of the unseen and explore how our bodies react and act on these sounds. This was the first work I made since I had moved to Berlin from Nairobi. I found myself in a limbo state, constantly thinking about how sounds and noises affect how I think and feel in relation to my new environment. I realised there weren’t as many sounds in Berlin, and I stopped making as many field recordings as I did in Nairobi. I became more focused on listening and being out there, thinking about my own presence in the environment.

S: Can you tell us some more about those electromagnetic recordings?

K: I used a microphone called the Ether. It has two antennas and captures many frequencies – anything electromagnetic or conductive. I also used some contact microphones, which I was recording on devices in Nairobi. The piece is a collage of both Nairobi and Berlin.

T: Has moving to Berlin made you look for any different sources of sound that you probably wouldn’t have previously sought after?

K: I think my music became a bit louder. Which is funny, because the silence of my environment made me want to embrace harshness and loudness more.

S: Speaking of loudness and harshness: your project with Aho Ssan, Limen, is “an attempt to scrutinize the yin and yang of destruction and creation”. What did you learn or find about that in the creation, release and presentation of the project?

K: That project was so exciting to make. While making it, Aho Ssan and I were thinking about the extremeness of sound. We wanted to reach the threshold of sound, stay on the tip of it and don’t break that balance. Aho Ssan’s approach of destructive synthesis inspired me a lot. I was exploring a lot of distortion and saturation. There’s this idea of noise versus nature. For example, people don’t want to deal with aeroplane noise, because they think it’s a bad sound. I don’t want to differentiate between a good sound and a bad one. There’s noise music, which can be abrasive, but at the same time very soothing to people. Finding a connection with some gnarly noise carries an emotional weight. So, In Limen, there’s this weightiness of emotion, but there’s also destruction. We thought about how volcanoes and lava form and reform, create, die and live again. We never planned to perform the project live, but it felt right to explore this on stage. The project has been constantly inspiring, from conception until now.

S: In another project of yours, Temporary Stored, you explore immaterial heritage, the endurance and continuation of colonial violence and the re-appropriation of stolen sounds through shorter fixed media pieces and a single longform radiophonic piece. Can you tell us more why the project was presented in this particular way?

K: Temporary Stored has been a constant conversation. Something I’ve been thinking about for quite some time. I think last year is when I decided to engage with the archive [of the Sound Archive of Royal Museum of Central Africa]. I realized that museums also store sound, rather than only objects. I felt that I needed to explore that, because the museums mostly made the recordings only accessible to researchers. Initially I just wanted to make the six tracks, but at the same time I wanted to try and tell a story from the archives in a longform format. I find that for long durational pieces, listeners will have to be present and listen to the entire work. I appreciate that aspect. For Temporary Stored I was trying to make an archive film with sound, and engage in the discourse of repatriation.

T: It’s inspiring to see this attempt to re-appropriate stolen immaterial heritage. But you’ve expressed that many back in Nairobi find your current form of music to be ‘weird’ or maybe not African enough. I was thinking, since you’re re appropriating these sounds and putting them in this ambient form: how would this project be received in Nairobi?

K: It’s funny because musicians in the scene of Nairobi found my music weird, but in a good way. I appreciate the thought that my music was weird.

T: So it wasn’t an outright rejection, but was just acknowledged as different?

K: I actually want to present this specific project in Nairobi, in the form of an installation. I think that a while back the scene was quite rigid, but has changed a lot. I’m excited to meet new people when I get back in 2023.

T: What do you think has been contributing to the change in the scene?

K: I think people realise there’s more to do with sound. At one point I felt the scene was quite homogenous. It had stagnated a bit with only a few artists exploring new sounds. Now, it has turned into a massive pool of new artists doing all sorts of music. There’s also a lot more resources through different people and platforms.

S: Your recordings truly feel as if they capture the spirit of a moment and a particular space. Field recordings really help in that transportative quality, of course. I’ve also read about how sounds work best for you to learn about your surroundings – like we discussed with regards to your move to Berlin. Why is sound so important to you in relation to exploring and understanding space?

K: It’s because we live in a very visual culture – to the point where we forget about sound. During COVID it became apparent sounds are constantly around us. Throughout field recordings I realised art is in so much of the sounds around me. I felt like I needed to use these sounds in my music and find a way in which I can communicate them to the listeners and audience. Eventually I came across the discourse of field recording and sound art, which was a new world for me. One for which I moved to Berlin: to start my masters’ degree in sound studies. It has been a constant listening practice for me.

S: I’ve been doing some field recordings myself as well. Sometimes the act of recording makes me lose track of my own position within the space. In some ways it feels like a barrier to the outside world, and in other ways it feels like some sort of superpower that enables you to hear all these different things. How does it feel to you, wandering around with headphones and a microphone?

K: I like how you call it a superpower. You have control over the environment, by deciding how much you want to hear. With regards to electromagnetic microphones, or contact mics, there’s this power one has of being able to record these unheard vibrations. But, I think it depends on the intention of what you want to do with them. Also, there aren’t so many people in the streets with field recorders. It’s a new thing. It’s not a device like a camera, that people know of, so people sometimes got a bit scared. I’ve had situations in Nairobi where people were asking me if I was using a device to bomb a place, or if it’s detecting radioactive material.

T: I was thinking about the consent to be listened to, or to be heard. And, I came across an interview where you stated that back home some would express their desire to not be recorded while some welcomed your recording. Did the resistance inspire any thoughts on consent when it comes to audio recordings, especially in a public space? When looking at photography there are many schools of thought on this topic, but I feel that it can become even more muddled when thinking about the realm of the sonic.

K: I think because sound is so ephemeral and intangible, the idea of ownership becomes strange. In Nairobi, I was doing this project which consisted of soundwork and field recordings in this slum. I was walking through different areas with a friend. We went to a kiosk, for example, and I mentioned that I wished to record the sound of the tailor working. Some would say no, and I’d understand the situation and be alright with it. I think it’s also about the intentionality of recording, or being in, spaces. Sometimes you feel that the environment does not need to be recorded, or you feel unwelcome. There’s always a feeling, before hitting ‘record’. I ask myself why I am recording a space. It’s a similar feeling to when I moved to Berlin. There was a bigger urgency to listen and be a part of the soundscape, rather than recording it. To attune myself and feel comfortable within a new place.

T: So it’s pretty much based on your gut feeling of the context, of where you’re in? It’s not this thing where you just go and explicitly ask whoever’s around whether it is okay to record or not?

K: Yes, but I think in specific contexts there’s always an initial conversation that you have with a group of people in a certain space. But most times, because I’m always alone with a recording instrument, it’s a gut feeling when considering the permission to record a place.

T: Can you expand on the idea of listening as an artistic practice?

K: In academia, as a standard practice, listening has become a catchphrase where we should listen to understand. But, I also realise that listening is very hierarchical and it is dependent on cultural background. It’s more silent in Berlin and noisier in Nairobi. Even in conversations you notice how communication with other people is different. I’m finding ways in which all of these listening practices can connect with each other, through the use of sound as the medium. It invites people to engage more with a piece of work. I think that’s why sound is quite important. In the art world, the more tangible things are the ones which are appreciated most. But, I think there’s also information or knowledge to be gained from sound and listening practices.